Even the most magical early stories of Hans Christian Andersen had, like most fairy tales, focused on, well, people and other living creatures. That is, what fairy tales were supposed to be about, at least, until then—creatures both imaginary and real who could talk and move. But in 1838, Andersen tried something a little different: a fairy tale about inanimate objects. Specifically, a tale about a tin soldier who could not talk or move.

In English, that was mostly translated to “steadfast.”

By this time, Andersen had already published several tales. None were overly popular, and none made him money, but they were enough to give Andersen a certain confidence in his craft. The idea of inanimate toys coming to life was not precisely new. Talking dolls were, if not exactly a staple of folklore, found in various oral tales, and had crept into some of the French salon literary fairy tales. Andersen had also presumably at least heard of E.T.A. Hoffman’s 1816 Nussknacker und Mausekönig (The Nutcracker and the Mouse King), which plays on that concept, and quite possibly read the tale in the original German or in translation.

But in most of those tales, the dolls and other toys, well, talked, interacting with other characters both positively and negatively. Andersen’s story had some of this, with toys that wake up in the night to play. But rather than focusing on the moving toys, capable of acting on and changing things, Andersen focused on the immobile one, incapable of changing things, and always acted on.

The toy in question is made of tin. Like many toys of the period, it’s not all that well made—one leg is missing. Andersen’s own father suffered ill health after a stint in the Danish army, and Andersen—and his readers—had certainly encountered numerous soldiers who had lost limbs, including legs, in the Napoleonic Wars, one reason why wounded, disabled and completely financially broke soldiers formed a minor theme in Andersen’s work.

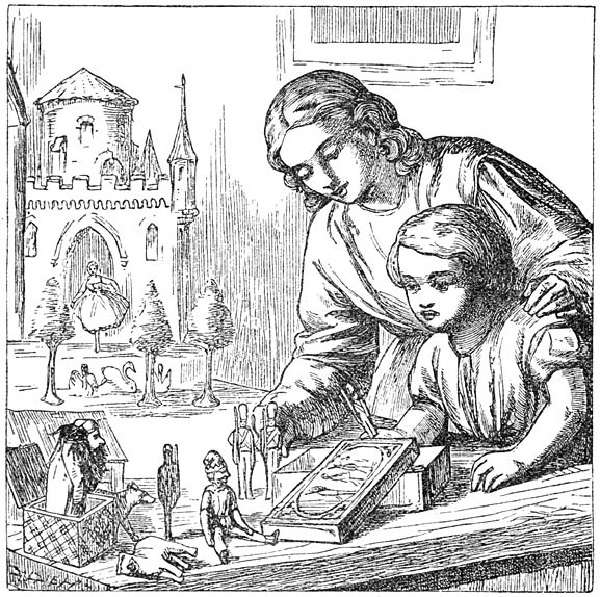

Still, missing leg or no missing leg, the toy soldier is still part of the toy soldier army, and is placed up on a table along with twenty-four two-legged toy soldiers. This gives him a good view of a cheap paper castle, and a paper doll who—from a distance—seems also to have only one leg. Based solely on this distant look and the assumption that the paper doll shares his one-legged existence, the tin soldier decides that she is the wife for him, like, generally speaking, at least exchanging brief hellos first might be a better first step. And in the only move he makes during the entire story, he lies down (or perhaps falls down) behind a snuff box so he can remain hidden and stare at the paper doll, which, CREEPY, tin soldier. I am losing my sympathy here.

I’m not the only person to object to this romance. After midnight, when almost all of the toys—except for the rest of the tin soldiers, locked away in their box for the night—come out to play, so does a creature translated as either a goblin or a troll. He is dark, and terrifying, and he warns the tin solder not to wish for things that do not belong to him. The soldier doesn’t listen.

The next day, he falls out of the window. He is found by two other boys, who place him in a paper boat and send him sailing down a gutter. By a series of what the story might call coincidences and I will call unlikely, the soldier eventually finds himself swallowed by a fish which just happens to get caught and which just happens to get sold to the family that originally owned the tin soldier which just happens to find the soldier in the fish. They are not as impressed as they should be by this; one of the kids even ends up throwing the tin soldier into a fire, where he starts to melt. The paper doll soon follows him; they burn and melt together.

I mean, even by Andersen’s not exactly cheerful standards, this? Is brutal.

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

Various critics have read the tale as a mirror of Andersen’s own not overly happy attempts to get a job at the Royal Theatre, where he was eventually rejected because, as the theatre put it, he lacked both the necessary appearance and the necessary acting skills for the stage. His later attempts to learn singing and dancing to compensate for his perceived lack of acting skill went nowhere, leaving Andersen watching the theatre at a distance—much the same way that the tin soldier never enters the cheap paper castle. The tin soldier’s inability to say a single word to the paper doll also echoes at least some of Andersen’s romances with both genders, romances that tended to be less mutual and more things Andersen thought about. (Though in all fairness to Andersen not one story even hints that a real life woman followed him into the flames, so, it’s not that close of an echo.)

But this seems to me to be less of Andersen remembering his stage training, and more Andersen trying to argue that what happened to him—and to others—was not his fault, but rather, the fault of circumstances and people outside of his control: evil, demonic entities, the weather, animals, children, and more. It doesn’t quite work, largely because Andersen also provides a hint that the tin soldier is facing the consequences of not listening to the demon (not to mention deciding that a paper doll he’s never even spoken to should be his wife).

And it doesn’t quite work because, as the story clarifies, the other toys in the room can and do move. Granted, only after the humans in the house have gone to bed, and they cannot be seen—a situation that does not apply to most of the toy soldier’s life. Given those conditions, he could not have escaped getting thrown into the fire, for instance. But since, in this story, toys can move when no one can see them, and since it’s safe to say that the soldier could not have been seen while in the stomach of a large fish, well. It would have ruined the biblical connection to Jonah, of course, but it would have been possible.

Which raises the question—why does the soldier never move, outside of that one moment when he hides himself behind a box to watch the paper doll? Especially since he has a reason to move—that interest (I can’t really call it love) in the little paper doll? His missing leg? Perhaps, though the rest of the tale seems to argue that a disability isn’t a barrier to love, travel and adventures—not to mention surviving getting eaten by a fish—so, that alone can’t be it. Nor can it be an argument for a complete acceptance of fate and everything that happens to you—after all, that acceptance leads to the soldier ending up completely melted.

Mostly, this strikes me as a story written by someone gaining more confidence in his craft, a confidence that allowed him to write a story with a completely mute and passive protagonist—a protagonist who can only think, not do. A story that works as literary experiment and fairy tale. It may not be one of Andersen’s more cheerful tales, but for all my nitpicks and questions, it may be one of his more successful ones.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.